A Piece of My Writing: No Information or Access

I was asked recently, by a dear friend, fellow adoptee, and professional psychologist, who is working with adoptees all ages, to give my input on what it’s like, how I process, and what advice I would give to an adoptee who has no access to their history, their origin, first family or circumstances around the reason for being adopted. And who may possibly never achieve any of those things.

I want to address that question as we enter NAAM19, and adoptees will be speaking about what adoption means to us. Not having access to your story makes it hard for many adoptees to ever gain a true sense of self. Anne Heffron expressed it perfectly in a meme once when she wrote that if you take a book, rip out the first chapter or two, lock away the pages and tell a person that those pages make no difference to the story. That is something along the lines of what many adoptees encounter when trying to find out our own story. Doesn’t make sense for someone wanting to read a book, does it? Well, it doesn’t make sense for adoptees when thinking of our own life either. And for many of us, those ripped out pages are just as important to our story, and even to our experiencing ourselves as real, as they would have been to the story in the book.

Be it amended birth certificates that are sealed, locked away and access denied, or falsified documents of a child to be adopted, or just plain carelessness to keep proper records, the results are the same. A child who grows into an adult, who on top of everything else, has had his or her own history edited or erased. Add to this, the potential of never being able to have access to any of it. The chance that any trace was wiped so clean that short of a DNA-test, which in turn depends on both parties actually taking and submitting one, there is no way of finding one’s family and ever knowing one’s own story. That is the sad truth for many transnational adoptees, and possibly domestic adoptees as well.

In my own case, for example, I don’t have a lot of information, and none of it specific, if I want to search. My name was given to me after I was “found”, my birthday was determined by doctors who examined me after I was “found”, and my story is that I was “found” and handed over to the police in Medellin, Colombia by an unknown woman. That is it. I write found with quotation marks, because I don’t believe that to be my true story. If my family is searching for me, they search based on the information they have about the girl that they lost. If I search, I do so based on the information I have, and though I am their girl, we are searching based on information that does not match. You can see how that can make things not only difficult, but actually impossible.

So, when asked this question recently, the answer I wrote back to my friend was this:

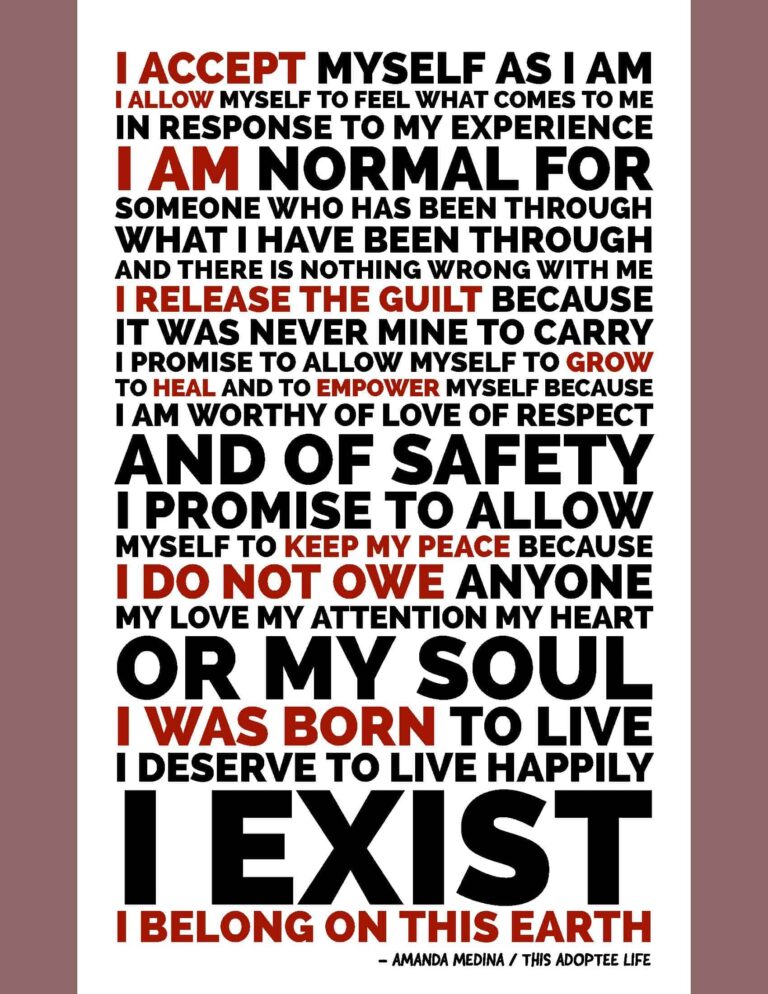

I think first and foremost I would say that I give myself permission not to ever fully come to terms with, or accept, that I don’t have access or may never have access to my full story.

The things that I don’t know, are things that define my life. I don’t know who gave birth to me. I don’t know wo my mother is. I don’t know where I was born. I don’t know what day I was born. I don’t know where or who I come from, what I have inherited, how or by who I was conceived and given life. I don’t know what my first year and half (or so) of life was like, and I don’t have anyone who I can ask that can tell me. I don’t know ANYTHING about my first year and a half of being alive and absolutely nothing about what came before. All I know is that I was adopted. That is where my story begins. Anything before that, I can’t verify or know to be the truth about me or my life.

That said, there is a chance my story is there, accessible. I have seen it happen for fellow adoptees. They live their whole life searching, turning every stone, hitting dead-end after dead-end, until they reach a stage of acceptance from defeat. They say they have tried everything. They say they must accept the fact that they may never find their mother, their family and therefore may never find the answers to their questions. May never know their origin or their own story in full.

And then they do. They make another attempt. And they find their family. After a lifetime of searching, after a lifetime of hoping, they find their family. After having come to terms with the idea of not ever being able to find access to their own story, and against all odds, they do.

So, I don’t know that I can say that I will ever reach a stage of full acceptance of the fact that I don’t have access to the possibility of one day finding my family and thereby finding the information that has always been missing. I think it comes down to a balance of accepting life as it is where you are now, while still allowing yourself to not ever lose hope or give up on the idea of possibly one day finding, if you are searching.

The thing with our adoptions as transnational adoptees, and I know for domestic as well many times, is that our paperwork can’t be trusted. So, while it may seem we have no story and no information, it doesn’t mean that we can’t one day get access to it. It won’t happen through the agencies or the authorities but may happen via DNA-test and PI’s. I think that for myself, rather than accept and close that door, I will work to prepare myself for the possibly long and emotionally draining task of searching.

It says in my papers that I was abandoned, but unless I get to hear that out of the mouth of the woman who gave birth to me, that she willingly abandoned me, I can’t trust that. There are so many cases of adoption, where it happened on false grounds. I could have been kidnapped. I could have been stolen. I could have been held for ransom by a childcare provider if my parents could not pay when coming to pick me up, and then passed on from there to be made adoptable. So, in other words, sold. The possibilities of me having been abandoned by my first mother, at her own choice, is one out of many other. And these other possibilities are just as likely to have been true.

I give myself permission to not accept that as my story, other than as being my past. Moving forward, I will not give up hope that maybe one day I will find my answers.

Maybe I am giving myself false hope and maybe I am approaching this with an open wound, risking having salt poured right into it. But I honestly feel the opposite is just as true, if not more. The primal wound is one that I will always carry and one that may never be healed. I have accepted THAT.

But to not ever be able to see my first mother.

To never be able to find out where I come from and who gave me life.

To not ever be able to know if the paperwork is true or if they are a lie.

That, I am not ready to accept.

If I knew for certain that there is absolutely no way for me to find out any information, then I would have to accept that and come to terms with that. But that would only be the case if I was able to find my family and no one in my family knew the information around my birth or my being separated from my mother. And even then, I’d know more than I do today.

So, for now, I give myself permission to not be okay with not knowing or having information and by doing so, keeping the hope alive that I may one day find out what I need to know to feel whole. And contrary to what might seem to be logic, that has made me calmer about the whole situation. I have removed the pressure to feel something I don’t. To reach a stage of acceptance I don’t think I will be able to reach until I have turned every stone and exhausted every option. I feel an acceptance for where my life is now, but not for what has been, nor for this being how it will always be.

I think that as adoptees we need to allow ourselves, and it would help if people around us, and society, allowed for us no to be okay, for us to have the internal struggles, let the emotions be what they are, and know that it is okay. Many times, a huge amount of the pressure we feel, comes from the idea that we must accept, even for ourselves, things that seem IMPOSSIBLE to accept.

And accepting THAT to be true then has helped me feel empowered in the moment and where I am in my life now.

Written by Amanda Medina

November 1, 2019

PS. We are all in this together!

Amanda Medina

About Us

This Adoptee Life is where adoptees can explore their story, share their experience, and speak their truth, in support and community with fellow adoptees, and the world.