Adoptee Story: Marycourtney N. Ning

Adoptee Story:

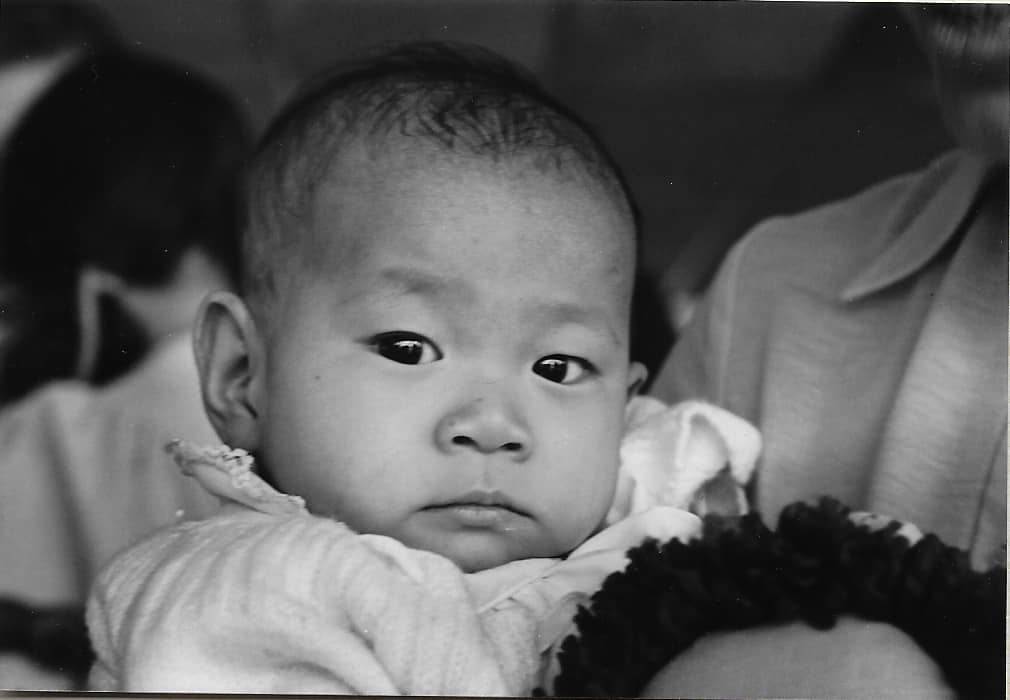

Marycourtney N. Ning, born in Vietnam, adopted to the United States

Intro: Sharing the adoptee story of Marycourtney Ngọc Quê Ning, in her own words. Marycourtney was adopted from Vietnam to the United States, during the war. Within her story, Marycourtney writes about survivor’s guilt, the reunion with a central character in her story and bringing to surface the entire, authentic and raw experience of life as a adoptee.

“Resilience Has Made Me Who I Am Today

When Amanda reached out and asked me to share my story, I was honored. I’m delighted there are other adoptees out there trying to understand their past and hopefully learning to deal with emotions that stem from trauma. So, before I begin my story, I would like to express a huge “Thank You!” to Amanda for creating a forum where we feel safe to share our stories and connect with one another.

My name is Marycourtney Ngọc Quê Ning and I’m in the process of writing a memoir about being a Vietnamese war orphan adopted to an American interracial couple during the Vietnam War. I recently launched an author website to help organize the process while writing my memoir: marycourtneyning.com.

As I began to blog more on the website, I realized not only was I delving into some very painful emotions, but I still have a long way to go to overcome the grief of an infant, orphaned in wartime conditions.

Dear reader, I think it’s important for you to understand why I don’t use the phrase “adoptive mother/father/family.” I was adopted around 6-9 months old; they are the only parents and family I have known so it doesn’t feel appropriate for me to use that terminology when referring to them.

In many ways, I was lucky to be adopted by an interracial couple; my father is second-generation Chinese and my mother is of Scandinavian descent. Thus, I didn’t grow up with the angst so many transracial adoptees feel—being an anomaly in an all-white adoptive family.

The choice to adopt a Vietnamese child was due to my father’s call to duty as a Medic during the Vietnam War. Unlike many Vietnam vets, he was never on the frontline of combat. Instead, he was assigned to Danang (aka China Beach). He spent most his time working as a local doctor for the orphanages, convents and monasteries. His favorite place was Sacred Heart Orphanage in Danang. His most cherished friendship was with Sister Angela, a Vietnamese nun of the French order who helped run the orphanage.

When my father returned to the United States, memories of the orphans haunted him. The connection to Sister Angela made Sacred Heart Orphanage an obvious choice once they decided to adopt. My parents went through a year of anguish—the Americans were still at war with the country so there was a lack of communication with adoption procedures. I was actually the third baby assigned to them.

The first baby died a week before she was scheduled to board the plane to America. The second was reclaimed by her mother before the paperwork was finalized. Both babies were half-Asian which made the process much easier. (The government only released babies that were fathered by Americans or Europeans.) When I arrived at Sacred Heart a few days after my birth, Sister Angela made a risky decision to “resurrect” the papers from the girl that died because I was full-blooded Vietnamese. Consequently, the birthday I celebrate is not mine. All information on my paperwork is from the baby who never survived. Sister Angela did change one thing on my paperwork; she christened me with my own name: Lê Thị Ngọc Quê.

How does it feel knowing I wasn’t the first baby chosen? Not to mention, knowing another infant had to die in order for me to have the fortunate life I do now. This is only the beginning of the survivor’s guilt I contend with every day.

In the 1970s, Vietnam had very little prosperity. With a war raging on, supplies and medical attention were almost nil. There were over three-hundred orphans and only thirty nuns to care for them; it wasn’t uncommon for more babies and children to die than thrive. By force of circumstance, very little human contact was given to the babies, most languished in metal cribs with bottles wired to the iron rods, in the hope that the children would learn to nurse themselves. It was a struggle to survive. Only the most determined children managed to live long enough to have papers processed and still endure the long flights to other countries where adoptive families anxiously awaited their arrivals.

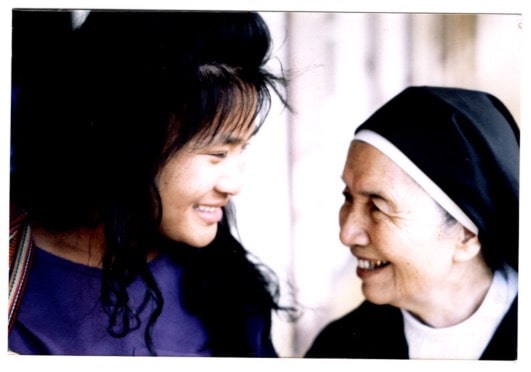

My knowledge of these circumstances came firsthand after meeting Sister Angela. Once adopted, my parents promised to stay in touch and raise me knowing my country, my people. Eighteen years later, I was the only baby to return to meet her. It was heartbreaking to learn about the atrocities, the conditions during those turbulent years; and the more difficult decisions Sister Angela made in order to ensure as many children as possible would survive.

In contrast to other adoptees, I don’t feel the need to search for my birth parents. I strongly believe my reunion with Sister Angela curbed this desire. Meeting her, I felt a sense of peace and knew she had been the closest relation to a mother I could claim. I learned about the orphanage’s history, the war’s effects on my village, and what I went through during the adoption process.

I’ve inherited the resilience of the Vietnamese people. Sister Angela’s strength and persistence resonate in me too. Shortly after our homecoming was delayed, we discovered she was dying. But the feisty Sister Angela promised to postpone her death until I could return a year later. We spent two emotional days together. We spoke brokenly—she’d been practicing her English, my French was still at high-school level. We mostly held hands, silently walking through the orphanage grounds that had been renovated into a day school for children.

Her death ten months after our reunion triggered my loss of the circumstances of my birth/adoption; and it’s been over thirty years since Sister Angela died. Although I’ve had issues originating from adoption trauma, it wasn’t until two years ago when I really opened myself up to examine the suffering I endured and its prevalence in past broken relationships, rifts with my family, and the inability to live to my full potential. By owning my story, telling my truth, and sharing with others, I hope to conquer these unexplainable fears and finally move forward to a better place emotionally.

Thank you dear readers, for continuing to listen and support adoptees and to celebrate all the emotions (both good and bad) that often arise with the adoption process.

All my best,

~mc”

Written by Marycourtney N. Ning

Marycourtney was born in Vietnam and adopted to the US

Marycourtney is a runner and a writer.

She is working on her memoir.

Find her and connect with her here:

Instagram: @marycourtneyning

and

her blog: www.marycourtneyning.com

Amanda Medina

About Us

This Adoptee Life is a place where adoptees can explore their story, share their experience, and express what they’ve lived through—supported by a community that understands.